Coerced resale price fixing distorts competition

All companies in the supply chain, from manufacturers, wholesalers/ distributors, to retailers, should enjoy the freedom to set prices for the products or services they offer.

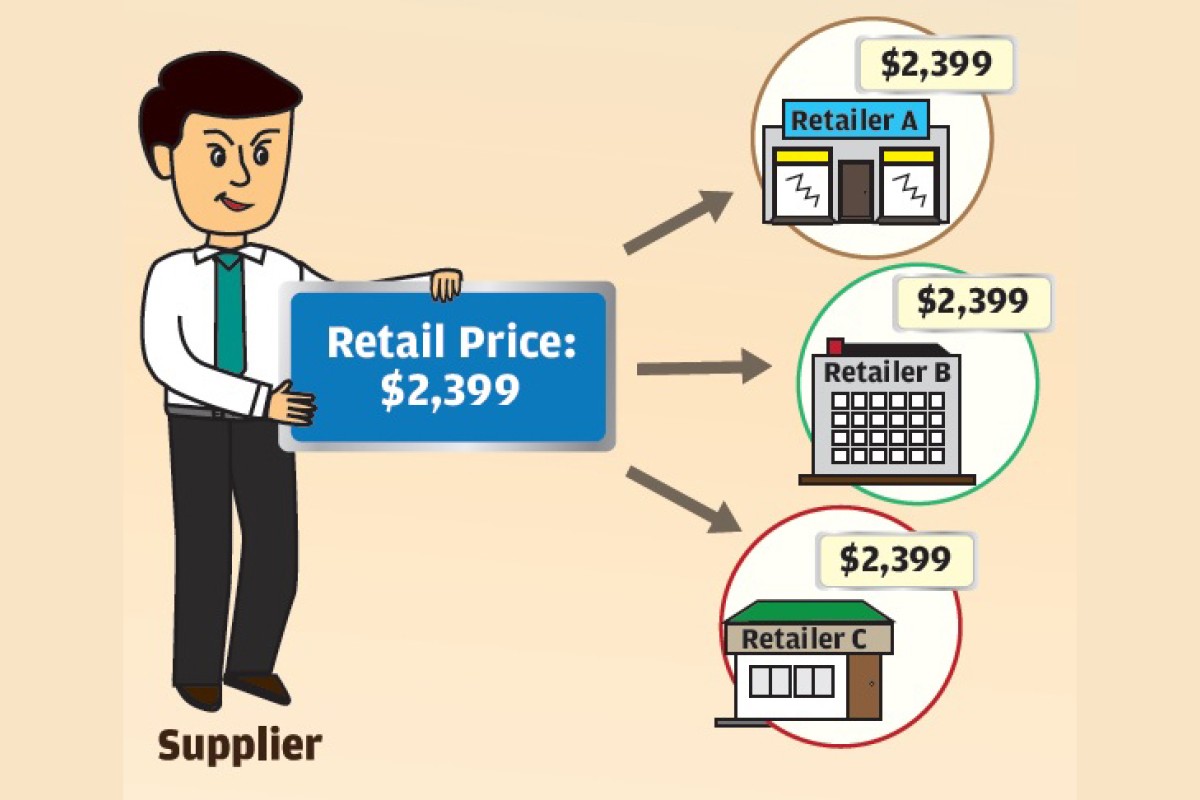

Resale price maintenance (RPM) occurs when a business (e.g. a manufacturer) tries to set the price, or impose a minimum price, at which its customer (e.g. a retailer) can sell an item. Such arrangements can undermine retailers’ pricing freedom and restrict them from competing with each other on price. As a result, consumers are denied the best prices that should result from an open and competitive market. RPM may run the risk of contravening the Competition Ordinance.

A supplier may use threats, warnings, penalties, or suspension of supplies to coerce retailers into a RPM arrangement. Or it can be implemented by a supplier in response to the pressure from another customer (such as a retailer) who seeks to limit competition at the resale level. In the following, you will see how the owner of the snack retail chain 759 Store was pressured by its supplier before the Competition Ordinance took effect in Hong Kong. Another case involved the large electrical goods manufacturer Mitsubishi in Japan which was convicted of RPM in Australia.

Forced price setting

In the early days of 759 Store, many suppliers were reluctant to supply goods to the chain because they found 759 selling their products at significantly lower retail prices compared with their other customers. On one occasion, according to the owner, when 759 set the price for distilled water at HK$2 per bottle at its Wong Tai Sin store, a distributor threatened him that unless he raised the price to HK$3, which was similar to that of nearby convenient stores, his supply would be cut off. 759 was then forced to reset the price to $2.8 in order to put out the fire. This is a typical case of how RPM denies consumers the access to more competitive prices without competition law.

Attempts to halt steep discount

In 2009, Mitsubishi Electric contacted its dealer Mannix Electrical in South Australia to express concern over the latter’s low retail price for its 7.1-kilowatt air conditioner. Mannix retailed the air conditioner at a 13.3-percent discount from the norm. Urged by Mannix’s retail competitors, Mitsubishi made attempts – referred to as ‘inducements’ – to influence Mannix to raise the price for this model of air conditioner and other prices it deemed too low. When this tactic proved unsuccessful, Mitsubishi terminated its supply contract with Mannix.

The Federal Court of Australia ruled Mitsubishi’s malpractices as RPM and imposed a heavy fine of A$2.2 million on the Japanese electrical manufacturer, reflecting the seriousness of its illegal conduct.

Prices for recommendation only

In today’s retail market, it’s common for suppliers to identify “suggested” or “recommended” retail prices. So long as they are merely recommendations, and retailers can freely adjust their prices upwards or downwards to compete with each other, they are very unlikely to raise competition concerns. It is also unlikely to harm competition when a fixed resale price is introduced for a short introductory promotional period in order to allow a new product to establish itself in the market.

However, where a so-called “recommended retail price” is combined with measures that effectively require the retailers to follow the recommendation, it may be assessed as RPM. Examples of such measures include the use of a price monitoring system or an obligation on the retailers to report those who deviate from the recommendation, and the retailer might suffer some form of penalty or adverse consequences should it depart from the “recommended retail price”.

Did you know?

Prior to the full commencement of the Competition Ordinance, the Competition Commission published an Enforcement Policy, which has guided its choices and prioritisation of cases. According to the Policy, resources will be focused on matters where most harm is caused to competition, and where most benefit will result to consumers. In addition, the Commission will seek resolutions that are proportionate to the nature of the conduct and the harm caused or likely to occur.

What happens abroad?

In many countries, competition law aims to protect against not only abuses of dominance and anti-competitive agreements, but also anti-competitive mergers between competitors. Companies will often be required to file their mergers with the relevant competition authority before they can proceed to close the transaction. If the competition authority gives the deal the “all clear”, they are free to go ahead. In Hong Kong, merger control applies only in the telecommunications sector at the moment.

Win a study trip to Singapore

Secondary four/ five students (or equivalent) and their teachers can now enter the “Don’t Cheat. Compete” Advocacy Contest by forming teams to create stories that illustrate the benefits of competition law. The top three winning teams will go on a study tour to Singapore. Act fast, registration ends on April 13, 2017.