Going to a clinic for a vaccine shot may no longer be necessary with this technology that's now in development

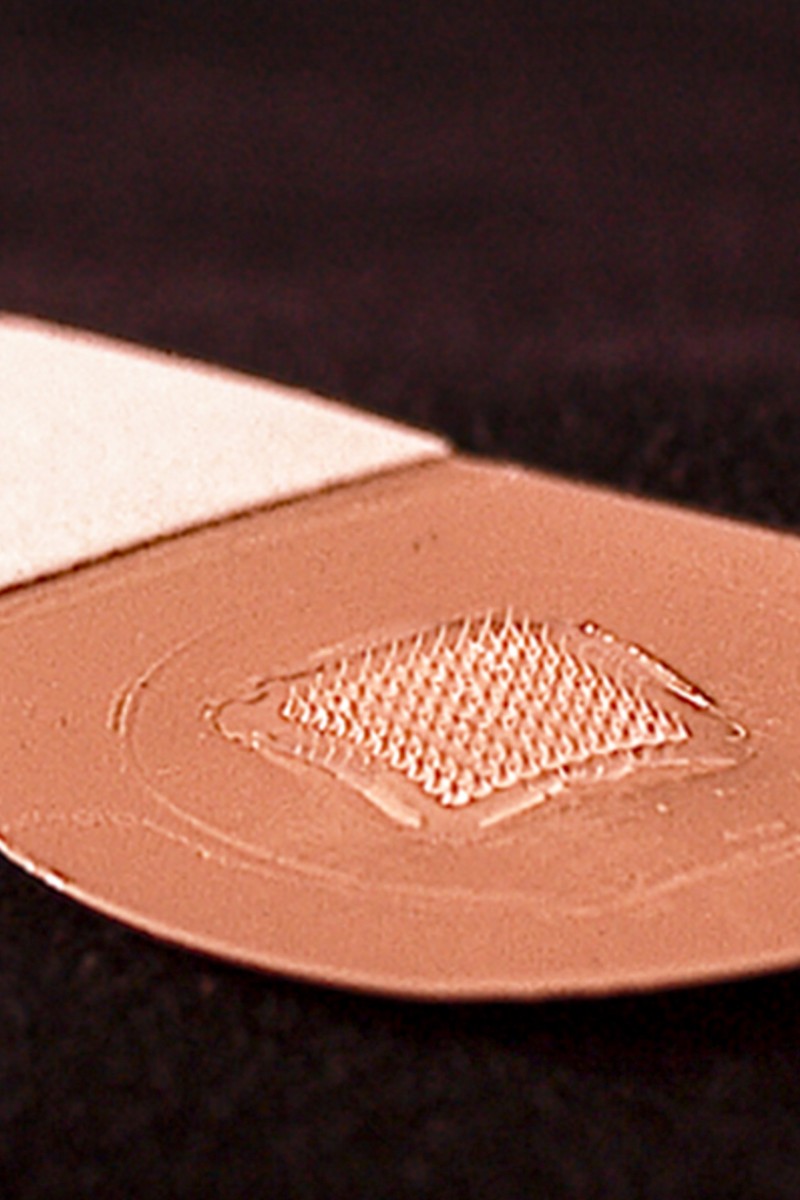

A prototype of a bandage patch that has microscopic needles which would deliver a vaccine.

A prototype of a bandage patch that has microscopic needles which would deliver a vaccine.When the next deadly pandemic flu hits, the first challenge will be to develop a vaccine. But looming behind that obstacle is another: how to get an inoculation to millions of people without inadvertently exacerbating the crisis.

After all, droves of people – some perhaps already sickened – who flock to health centres for a shot could be a potent way for the infection to spread.

On the 100th anniversary of the influenza pandemic of 1918 that infected a third of the world’s population and killed 50 million people, vaccine researchers are searching urgently for new approaches to prepare for the next pandemic – a threat most public health officials consider inevitable.

Let’s make the HPV vaccine free in Hong Kong

A new study provides proof of concept for a solution that could upend the traditional centralised model, in which health professionals give injections at clinics.

Researchers created an H5N1 vaccine, boosted by a special ingredient that primes the body’s immune system to respond. Then they administered it through a microneedle that penetrates only the skin’s upper layer. They see this prototype technology as a platform that could lead to novel vaccine patches that can be distributed rapidly and administered without a nurse. People would stick a bandage-like strip, lined with microscopic needles, onto their skin.

“It’s an excellent, extremely comprehensive and well-done study,” said Mark Poznansky, director of the Vaccine and Immunotherapy Centre at Massachusetts General Hospital in the US. He was not involved in the research, published in Science Advances. “What they’re suggesting is something you could stick in an envelope and get to people rapidly – it’s an important breakthrough technology.”

The research team combined several different technologies into their prototype: tiny, hollow microneedles that penetrate only the upper layer of the skin were paired with vaccines made from non-infectious “virus-like particles” that can be rapidly produced by tobacco plants. Crucially, researchers added another ingredient, called an adjuvant, that speeds up and strengthens the body’s response to the vaccine.

The study, funded by the US Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency, is still at an early stage. Large-scale human trials will be needed to determine the safety of the approach, which successfully protected ferrets from H5N1 and appeared safe in a small human trial to study safety.

Darrick Carter, a biochemist at the Infectious Disease Research Institute in Seattle, said that one of the most exciting things their study showed was that the adjuvant seemed to confer protection against not just the target virus but also related viruses.

A lesson on animal research and their role in vaccine development

If that observation is borne out in further studies, it could address an important problem in vaccine development. If the strain of virus used to create the vaccine mismatches the pathogen that is circulating, the vaccine becomes much less effective. The 2016-2017 flu vaccine, for example, was only moderately effective because of a mutation in the virus.

Because public health officials seeking to prepare for a pandemic flu won’t know the exact strain in advance and the virus could change during an outbreak, vaccines that could be made more broadly effective with an adjuvant are exciting to researchers.

“If you think about the mechanics of how the stockpile is done, with a single virus and millions of doses – the probability of that exact virus emerging is, in my mind, fairly low,” Carter said.

Carter and colleagues plan to apply the technology to an area of medicine where funding is typically more accessible: cancer. They hope that the adjuvant that stimulates the immune system could, if injected into a tumour, awaken the body’s immune cells to attack the tumour.