The Galaxy Note 7 is no longer being produced or sold – but why have there been so many incidents of the batteries causing them to catch fire or explode?

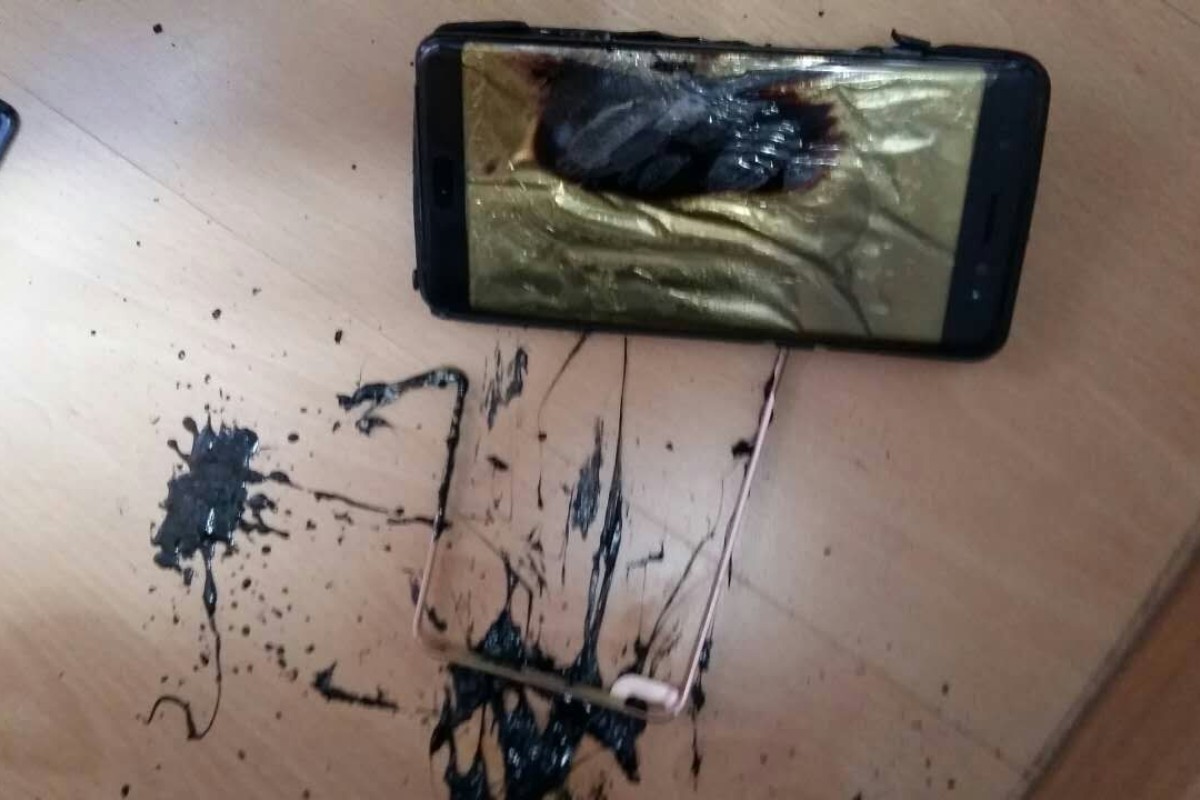

A Samsung Galaxy Noted 7 mobile phone explosion during its battery charging.

A Samsung Galaxy Noted 7 mobile phone explosion during its battery charging.South Korean tech giant Samsung has told customers worldwide to stop using their Galaxy Note 7 smartphones after a spate of battery explosions threatens to derail the powerhouse global brand.

It is the latest in a string of lithium-ion battery fires on products ranging from laptops to hoverboards to planes – and a reminder that pushing technology can sometimes be problematic.

Here are some things to know about Samsung’s safety crisis, the recall and halt on production of Note 7 and why batteries can be a fire hazard.

A lithium-ion battery is a kind of rechargeable battery that uses different materials, one holding positive ions – the cathode – and the other holding negative ions – the anode. These ions move one way when charging, and back again when discharging (when the phone is being used).

These two layers – or conductors – are never supposed to touch, so manufacturers insert separators to keep them apart. Unfortunately, the chemical reaction that makes batteries work also creates heat. Overcharging the packs, or charging them too fast, can lead to fires.

Samsung has said parts of the battery in the Note 7 that should never touch came together due to a “very rare manufacturing process error”.

Gadget makers weigh all sorts of factors like performance, cost and safety when rolling out technology.

And the race to push more battery life into their latest phone or tablet can lead to unexpected results.

“Smartphone makers are trying to squeeze these batteries into a small, thin package,” said Hideki Yasuda, an analyst at Ace Research Institute in Tokyo. “Since batteries generate energy through a chemical reaction, it’s really hard to reduce the risk (of fire) to zero.

“Sometimes convenience comes with a price.”

Battery fires have been reported in products including Sony Vaio laptops, last year’s must-have toy the hoverboard, electric bikes and even Boeing’s Dreamliner jet.

In Samsung’s case, faulty batteries caused some handsets to burst into flames during charging.

More cases of exploding batteries continued to emerge following the recall announcement, with users claiming a burning device had damaged a hotel room in Australia or set a car on fire in the US.

Millions of lithium-ion batteries are produced annually with a tiny fraction of those catching fire or exploding.

At the start of September Samsung had received reports of about 35 incidents involving the phone’s batteries, with the tech giant launching a recall of 2.5 million Notes 7s in 10 markets. The firm said it would exchange the devices but there have been troubling reports that the batteries in the new handsets have also been involved in fires.

“It’s not easy to know if Samsung’s problem is the same as others ... at this point,” Yasuda said. “If its battery suppliers sell these same ones to other producers, it could possibly affect them too.”

According to some analysts, the cost of the Samsung recall operation could be up to $2 billion.

Although the company issued a stronger-than-expected operating profit forecast for the third quarter earlier this month despite the Note 7 setback, it has been battered by slumps in share price over its exploding smartphone woes.

The US Federal Aviation Administration has also issued a guidance update, urging all passengers to power off, and not use, charge, or stow in checked baggage, all Samsung Galaxy Note 7 devices. That’s whether or not they are the originals or replacements.

The scandal will also put pressure on other gadget makers to figure out how to make battery packs safe for ever-smaller devices.

“We always want batteries to be safe but also to be more efficient,” said Guy Marlair, a France-based safety expert. “The more that we boost the battery’s performance, the higher the energy density in a small space and the tougher it is to manage security.”