Saving an arm and a leg: the science of prosthetic limbs

Once confined to sci-fi movies and tech expos, prosthetic limbs now improve many lives. Ariel Conant finds out about how one company is making the costly technology available to the masses

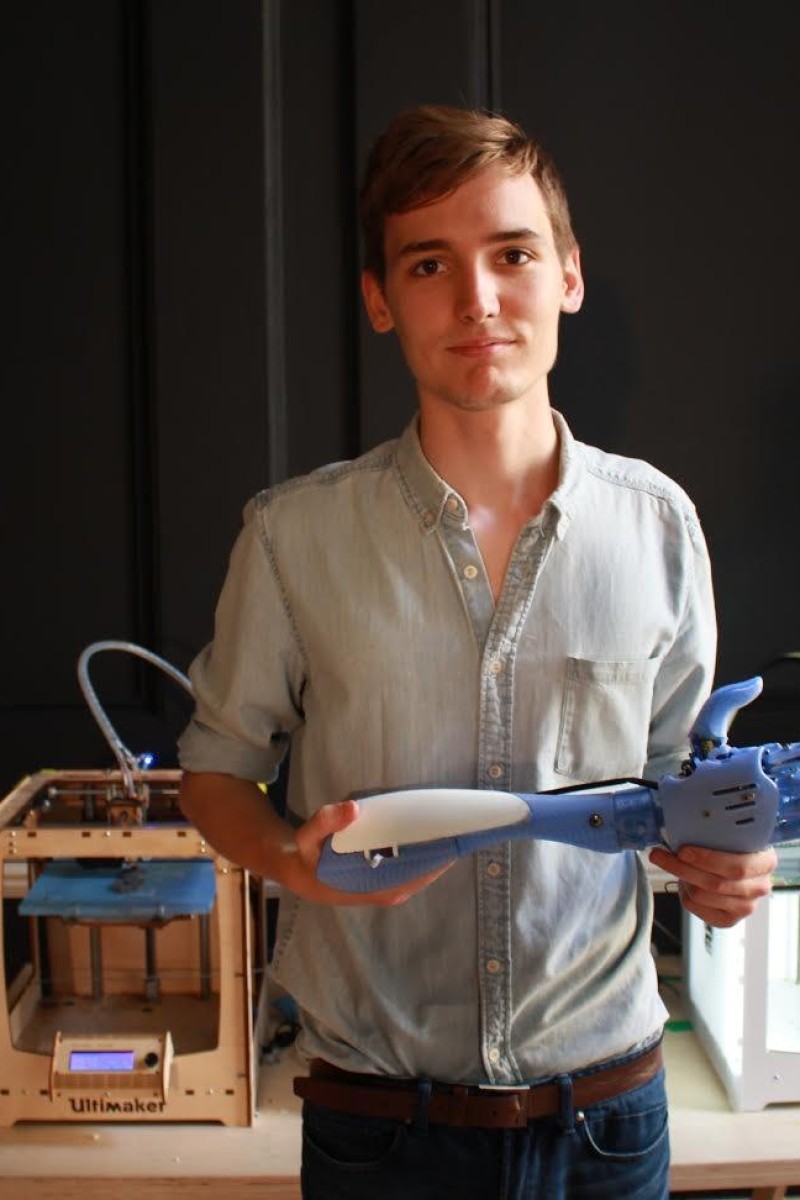

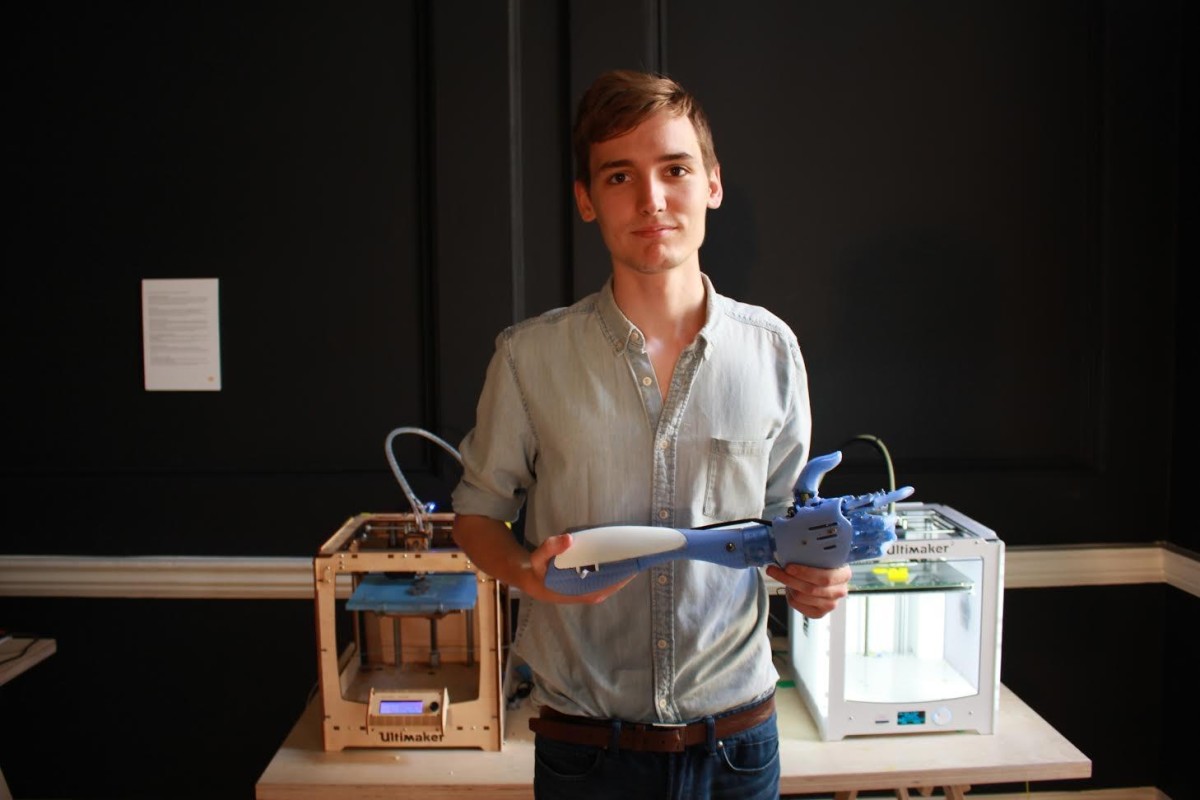

Cameron Norris with his arm prototype.

Cameron Norris with his arm prototype.Science fiction stories are filled with androids, robots and bionic arms or limbs that can make you better, faster, stronger. Luke Skywalker got a new hand in a galaxy far, far away and then could wield a lightsaber better than ever. But bionic arms are no longer a fantasy: real-life prosthetics have developed to mimic human limbs and are making the daily routine easier for many people worldwide.

But getting a new bionic limb can be costly, as only a few specialised companies currently produce them.

That's where Cameron Norris steps in.

The 24-year-old is Community Connector at the London-based web-based platform Wevolver, which specialises in sharing and collaborating on new technology hardware.

Their goal is to make blueprints available on the internet so anyone can access them.

One project Norris worked on through Wevolver was the exiii-HACKberry. Developed by Japanese robotics company exiii Inc., the HACKberry is a prosthetic arm that can be 3D-printed, and works like a real human arm by detecting when nerve and muscle tissue are stimulated. This allows the wearer to control movement of the hands and even individual fingers.

But no one outside of exiii Inc. had ever tried printing one before Norris. After seeing a post on an online forum about a weight-lifter, Ryan Cashman, who lost both hands in an oil rig accident, Norris saw the opportunity to put the HACKberry plans into real-life action.

He contacted Cashman, who lives in Texas, US, and offered to build him his own custom HACKberry prosthesis, which would in theory allow him to continue his hobby of weight lifting with the bionic technology. Cashman agreed, and Norris got to work.

"I studied marketing at university," Norris laughed when Young Post asked him about his background in electrical engineering. While he'd always had a fascination with putting things together and electronics, building this prosthesis was trickier than he'd imagined. "The fingers are intricate and hard to make. The shape has to be exactly right," he explains. "They're so delicate, all the electric work. Once, the fingers actually exploded while I was working on them."

But Norris was determined, and was able to successfully build a prototype of the HACKberry in just seven days. "I didn't sleep that last night, working to get it finished," he says. "It's an incredible design, and it's very accurate too. You can pick up tiny objects and tie shoelaces."

It was the first step in getting Cashman his prosthesis. Since this was the first prototype to ever have been built outside the company that designed it, exiii Inc immediately contacted Norris to congratulate him and offer their support for his project.

But Norris knew he would need more help if the project would was going to be a success. Turning back to the internet, he was able to put together a global team of eager professionals, including a prominent hand transplant surgeon in Australia, experts in carbon fibre and manufacturing from the United States, and an amputee who has been using prosthetics for over 15 years and helped advise on the project.

"It's really shown how we can all be part of a much bigger picture if we work together. It's also shown how typical divisions in society, such as race and religion, become almost meaningless when a group begins working towards a common goal," Cameron marvelled.

Along the way, Norris also learned about Rosa Moreno, a Mexican woman, who lost both arms after an accident at the factory she worked in. Her family was unable to afford prostheses, and without arms she is unable to work to support herself or her family.

Norris didn't hesitate: he expanded the project to build Moreno a new set of arms.

As the project grows and more people become involved, Norris sees the future of open-source technology opening up.

"I don't think that technology like this should be patented or restricted by people who want to make a lot of money out of it," he says.

"People's access to life-changing technology shouldn't be controlled by 'technological gatekeepers' who demand huge sums of money."