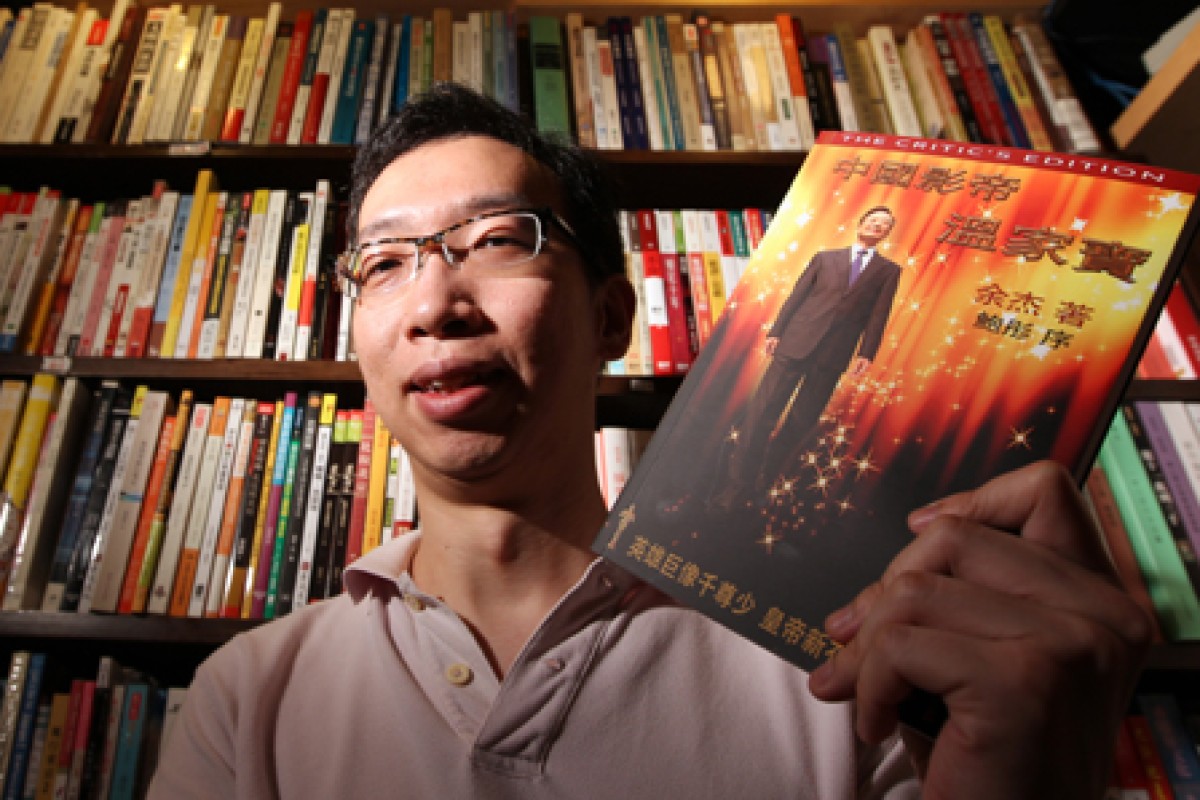

Paul Tang Tsz-keung, owner of People's Recreation Community in Causeway Bay, holds up China's best actor: Wen Jiabao, which is banned on the mainland.

Paul Tang Tsz-keung, owner of People's Recreation Community in Causeway Bay, holds up China's best actor: Wen Jiabao, which is banned on the mainland.Taking advantage of their newfound mobility, many mainlanders come here just to get their hands on banned titles.

One of their favourite hangouts is an upstairs bookstore called People's Recreation Community in Causeway Bay, opposite Times Square. Just look for the Chairman Mao icon.

Co-owner Paul Tang Tsz-keung set up the small shop in 2002 to sell Chinese literature from a vast genre.

When the Individual Visit Scheme extended in 2004, many mainlanders came asking after books they couldn't find at home. To cater to rising demand, Tang switched to the niche market of illegal tomes. "Now 90 per cent of our customers are from the mainland," Tang notes. "Many will buy as many as 10 books at a time, costing up to HK$1,000 in total."

The shelves groan with hundreds of both Chinese and English titles. The chart topper is Prisoner of the State: The Secret Journal of Premier Zhao Ziyang, which has sold nearly 130,000 copies in the city. Other highly sought-after titles include China's Best Actor: Wen Jiabao and The New Crown Prince Party.

Tang observes that different age groups have distinct interests. Older patrons seek out books about earlier periods of modern Chinese history such as the civil war and the Cultural Revolution. Younger generations prefer books about current and recent events such as the 18th National Congress.

"What they share in common is that they want to know more," Tang notes. "They want to [explore] things like Mao Zedong's and Zhou Enlai's darker side."

Bookstore regular Lu Wen is a Beijing native who studies in graduate school in Hong Kong. He thinks the books not only answer lingering questions but also give him a great deal to mull over.

"Living in a rather closed society, reading about unmentionable subjects makes me wonder how other people think about our leaders and how we should interpret the truth that has been covered up," Lu says.

Yet books published in Hong Kong may have their drawbacks for mainland readers. Characters are set vertically in the traditional way, not horizontally, Lu says, turning a book he holds sideways.

Taking books back home could be risky too. Beijing has not released an official list of banned titles, which makes for a huge grey area. Customs officers often take advantage of that by confiscating books.

A lot of the banned literature is available on the mainland in pirated photocopies in print or online as well as in individually copied editions. Lu thinks there is a huge market for such books. "If bookstores selling banned books open up in China one day," Lu says, "they will surely be chock-full of people."