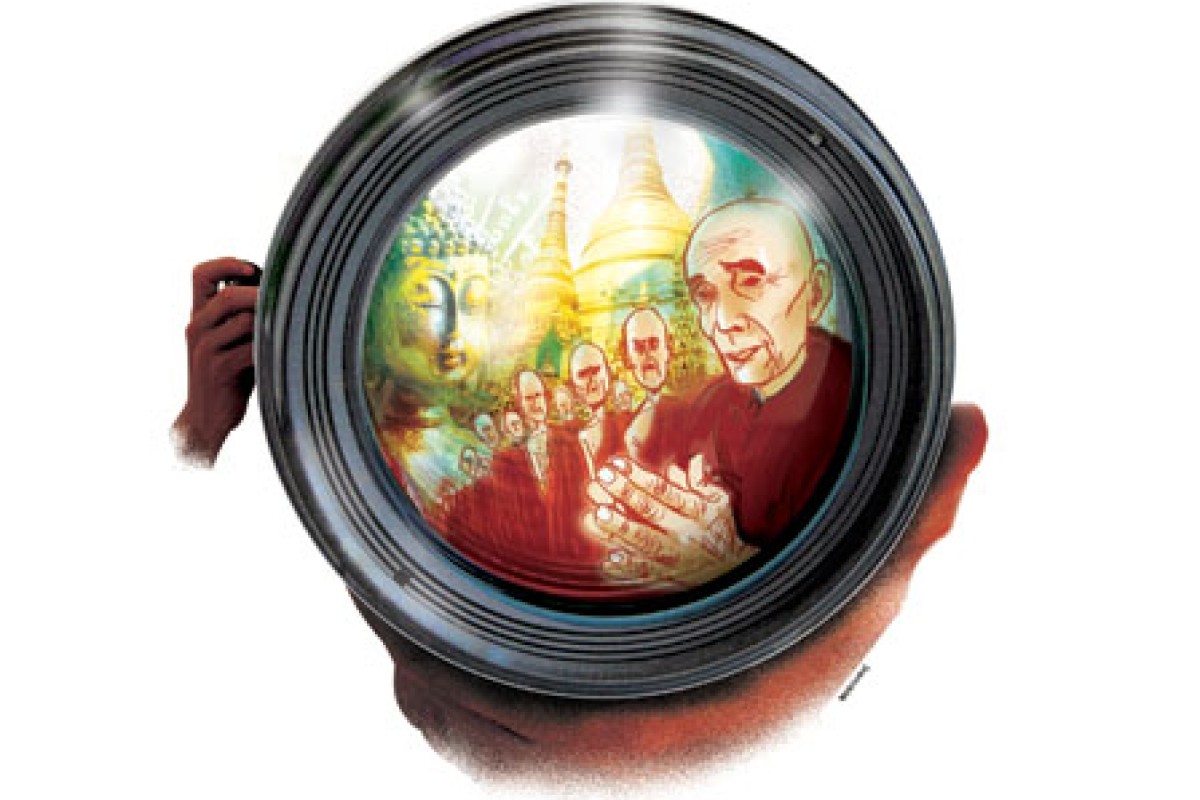

Mothers, clutching wary-eyed babies, watched the streets outside their windows. The betel-chewing men, who usually squatted by the road, were standing upright, expecting something to happen. Yesterday, the monks had marched in a flurry of saffron robes, banners and bare feet. Today, Myanmar eagerly awaited their return, and the world waited for Maung to wake up.

Maung woke to the discordant sounds of a Monday morning, and the thin stream of sunlight that crept through the blinds. Over the past two months, this had been his routine - seven straight hours of sleep until the street outside became noisy.

He sat up, eyes darting quickly from his sandals propped on the carpet to the cardboard box in the corner of the room, packed with cords, tangled wires, battery packs and two old video cameras that bore scratches and faded Sony logos.

He dressed and poured himself a cup of chocolate milk in the kitchen. Usually he had water in the mornings, more water in the afternoon and some beer at six o'clock. But today was a big day - the monks had come out, the people had marched to Aung San Suu Kyi's house, and he needed to stay vigilant. He took a pill from a bottle of vitamin C supplements his mother had found at a market at Mrauk U. She was always a pragmatist, his mother. Health came first, dignity and patriotism second.

His mother was a light sleeper, so Maung had learned to be silent in the mornings. His feet knew which creaking floorboards he could not tread on. If he did wake her up, she would automatically slip on her felt slippers and patter to the kitchen. She would sigh with wet, creased eyes, fix his collar and tell him to be careful and to come home by 10.

He cherished his mother's love and constant admonishment. But when he roamed Yangon, video camera in hand, her love restrained and saddened him. With a job like his, working under the constant scrutiny of the menacing junta, he couldn't let sadness get to him.

He grabbed one of the cameras from the box, and shoved it in his simple bag of unravelling straw.

Maung's home was in the centre of Yangon, and a line of robed monks and restless students already stretched along the street.

He stepped onto the uneven concrete and joined the line, his leather sandals in sync with the calloused soles of the feet of the monk in front of him. The monk, with an egg-shaped head and robes that hung too loosely on his shoulders, turned towards Maung, surprised.

"Min-ga-la-ba," Maung said.

The monk replied with a curt nod, his eyes darting nervously. His cheeks were smooth and clean-shaven, like Maung's. It was an innocent face, a face unfamiliar with adulthood.

"How are the marches going?"

"Even better than yesterday," the monk replied, "and the government is silent."

"Not tired yet?"

The monk smiled. "No, I'm not tired. While they raise prices to buy fuel for their tanks and ammunition for their guns, I will never be tired. But nervous, yes, nervous, of course."

"Yes, everybody is nervous."

"What about you, brother, what brings you here?"

Maung pursed his lips, then carefully reached into his satchel and pulled out his video camera. "My work. DVB."

The monk's smile disappeared and his pace quickened. When they reached the fork in the road, the demonstrators, with their banners, streamed into the park.

"You want to be careful with that, brother," the monk muttered, "the junta are everywhere."

He nodded subtly to two policemen, dressed in their familiar camouflage shirts and felt hats, clutching their shotguns and scanning the crowds. Maung thanked the monk and crept away from the line towards U Wiwara Street.

However, he did not put the camera away; instead he turned it on and began to record. Walking towards him, one of the policemen spotted the camera. Maung covered the lens quickly, shoved the camera into his jacket pocket and strolled briskly into the market street, diving into the throng of people.

During the lunch hour, he would have to lie low. Only later in the afternoon, when the crowd thickened, could he film. Be patient, Maung, his mother always said. Don't be too greedy.

His father had been too greedy. He went to work in the morning with his pudgy Nikon camera hanging lopsided at his waist, its lens, meticulously wiped every morning with a piece of cloth, perpetually shining. The streets of Yangon were covered in his footprints - he had captured anything he pleased: interviews with workers, all of Suu Kyi's speeches, snippets of junta men interrogating another DVB undercover reporter like himself. He went to all the rallies and protests, greedy for footage - he wanted the world to see Myanmar. Everyone had been familiar with the rasp of his voice, familiar with the tawny, incandescent flash of his camera. Maung's father had been an idealist. Let the world see the oppression of Myanmar, he used to drill into Maung every day.

He remembered his mother's face when his uncle knocked on their door that night seven and a half years ago. Her face was unresponsive and stony-eyed, almost indifferent, when she heard her husband was dead. Maung was surprised at her callousness, how reserved she was. But she was the pragmatist. She was the woman who stifled her tears. She was the wife who incessantly told her husband to relax, to be patient, to be a father. And now here was uncle telling her that her husband had been shot while trying to sneak into the Government Building with a camera in one hand. Two bullets, he said, one in the neck and one in the stomach.

By three o'clock, Maung was growing restless, sitting beside a fridge in a convenience store. He stepped onto the street and made his way to the park. The protests had escalated. The park smelled of the collective sweat of the protesters and the faded dye of the monks' robes. People were everywhere, pacing the streets and squatting on the sidewalk. A line of students leaned against the new building erected last year, an awkwardly placed slab of concrete in the middle of the city's most colourful, tumultuous area. Flags and placards adorned its whitewashed walls: "Killer Than Shwe!" and "Free Aung San Suu Kyi!" they read.

Maung inched his way through the crowd, looking for a good spot to film from. There was an old building opposite the park, with a low, flat rooftop. He knew the entrance was locked from the inside, so he decided to climb the fire escape that twisted up to the roof of the building. It was humid and hot, but he ran up the stairs, one hand tightly gripping his camera, the record button quivering under his nervous fingertips. When he reached the roof, he wiped the sweat from his forehead with the back of his sleeve, then looked down.

The sight took his breath away. From above, the park was a mosaic of crimson robes, raised fists and scarlet banners. The sun slanted in from the right, directly onto where the monks stood, so that their heads glistened. Wide-eyed children peeked out of the windows of apartment buildings, clapping so hard the palms of their hands were pink and raw. A cluster of women stood by the pavement, handing out plastic cups of water and popsicles. "Our cause! Our cause!" Their voices, the soft tenor of the monks and the throaty holler of the students, rang through the park, melding into one chorus - the voice of the frustrated, the voice of Myanmar. Entranced, Maung watched and listened.

Throughout, the camera stayed in his hand. It stayed in his hand even when he saw the trucks of the junta making their way into the park. It stayed in his hand even when he saw young soldiers hop out of the trucks, and when the loudspeaker announced anyone remaining in the park after five minutes would be shot. When the people didn't move, the guns were loaded. But the camera stayed in his hand, even as he heard the shots and the cacophony of cries.

He knew he should hide, sprint down the fire escape and run home, but he didn't. The camera was welded to his fingers. Instead, he stood on the rooftop and filmed the people disappear from the park, filmed the spent bullets on the ground. Let the world see, Maung. He filmed, feeling a gush of euphoria and pride, mingled with guilt.

He stood on the rooftop and filmed. When it was too dark to film, he climbed down the fire escape and walked home thinking of excuses to tell his mother.

It was an early September evening in Yangon. The footage was uploaded and swiftly on its way, from camera, via FireWire, to the rest of the world.

Yi-ling is a student at Chinese International School

<!--//--><![CDATA[// ><!-- PDRTJS_settings_2630434 = { "id" : "2630434", "unique_id" : "default", "title" : "", "permalink" : "" }; //--><!]]>