Everyone knows the environment is a big problem for Hong Kong, but one narrator takes the enxt step to consider what the city's future holds. This story was written by Yu Sze-hon from Tsuen Wan Government Secondary School

This is the winner of Young Post's 2015 Summer Story competition, and the author of this story will be receiving some marvellous books as his prize!

The vastness of the South China Sea stretched in front of me as I climbed out of the floating solar panel factory, followed by my friend and colleague, Chong, who was puffing from the ascent.

Nothing in particular had changed in the half hour since I had climbed down the same ladder to the factory which had cornered the market in solar cells. The sea was still as murky, and the air smelled of the acidic pollutants from the gigantic machines behind me, and even time itself, an ordinary day in April 2065, was still strolling at its own leisurely pace. And yet, everything had changed, and it was all because of the almost carpet-like solar cell that I had on my shoulder.

The boat trip from the factory to my home, hidden in the slum of the Kowloon Waters, was long, and was made even longer by my avid anticipation. Sometimes, I concluded, having the thing you'd been dying for, without being able to use it right away, was more of a torment than not having it at all.

For the first time ever, I was eager to return to my shabby home, to see the wrinkled face of my grandma crack into a smile, to plug the solar cell into the household electricity system that hadn't been used for decades and to say goodbye to the extortionate propane costs that had been squeezing us dry.

The ferry, originally trudging at a speed of no more than 10 knots, now slowed to a crawl as it gave way to one of the luxurious yachts, its exterior sparkling dazzlingly due to the expensive coating of photium, a self-illuminating alloy.

"If I saw this yacht yesterday," said Chong distantly, "I'd not even dream of either you or I on it. They all said we were the scum of Hong Kong, and I hadn't anything to show otherwise! Living in the floatainer, putting all that synthesised crap into my mouth, burning propane that makes more smoke than heat ... But look, now you've got something to lift you out of the poorest 10 per cent! Who knows, maybe in a few years it'll be you on the yacht!"

I carefully digested his words. Many a trillionaire boasted about how he had risen from being a mere factory worker or a shipbuilder's apprentice to being the most influential figure in the city (if only in his own eyes). With that in mind, I didn't see why I couldn't make money selling excess electricity with my ultra-efficient solar cell. After all, electricity was a commodity that was always in demand. It was hugely expensive to buy a solar panel, but once you had saved enough money to buy your own, you would hold the magnet for wealth in your hand.

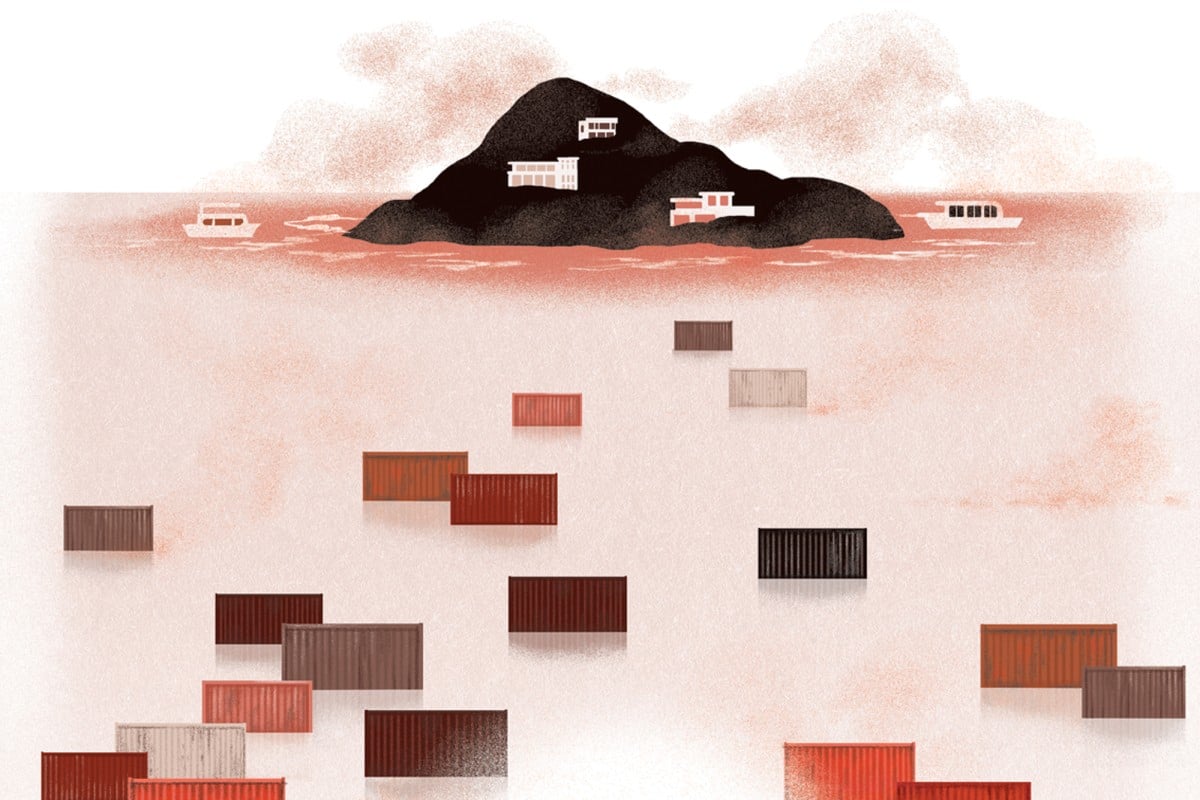

More and more photium-plated yachts appeared as we got closer to the Mid-Levels Coast, one of the only parts of Hong Kong Island to survive the Great Flood of 2043.

The solar cell factory, south of the Coast, was no longer visible, which was lucky as the steel grey monster would spoil the otherwise magnificent view enjoyed by the residents of the Coast. Thanks to its prominent inhabitants, the region was the most prestigious (and in fact the only decent) area in the city. Its eastern side was a dense cover of fancy mansions and seascrapers - buildings that extended underwater to the seabed - while its western side seemed to be completely untouched by humans, with soft hills and an unbroken expanse of green. My heart was bursting with happiness as I pictured myself sunbathing on the crescent golden beach of the Coast. Just now however, I couldn't even enter the water security perimeter of the Island, let alone set foot on it.

"Pirates," Chong hissed, as if the very word couldn't be spoken aloud. There was a hint of the pungent propane in the air, the work of the triple engines on the pirates' speedboat. Painted deep blue as camouflage, I only spotted it coming when it was just a few hundred metres from the ferry.

Our ferry, albeit big, was all rust and minor leakages and only had the antique diesel engine of the 20s. Its outdated design was never meant to operate in an atmosphere with only 14 per cent oxygen and 1 per cent carbon dioxide, leaving the engine gasping for air. The pirates, however, being very active in both the prestigious Hong Kong Island Waters and the impoverished Kowloon Waters, had grabbed a considerable number of quality spoils from the richer residents, including some propane engines. Far better equipped than us, it was only a matter of time before they caught up and boarded our ship.

I should have been shivering with fear, but I wasn't, and instead, almost took sadistic pleasure from watching others fidgeting in their seats. The only valuable I had was the solar cell. And I had spent half an hour in the factory setting up a series of complex security codes, inputting biological identifications using every single part of my body, and being showered with assurance that any trespasser intending to operate the panel would be pinpointed and arrested in no time. I felt as relaxed as the seagulls sunbathing on our ferry.

Somebody shouted, "Call H2PO [water police]! They'll rob us and throw us overboard. Call the ..." the voice died down as she realised the absurdity of her words. The H2PO was only responsible for the crimes within the security perimeter of Hong Kong Island, and outside that area, you could only pray that you didn't run into any bandits.

The ferry rocked as the pirates hooked their boat to ours. A swarm of men in tight-fitting, black, waterproof clothes stormed the boat, with steam guns radiating a metallic threat around their waists.

Watching the incident with the calmness of an outsider, I found that they amusingly reminded me of the Japanese ninjas, who had been popping up more and more often since the Great Flood. The Japanese had realised the roaring sea was the best training centre nature could offer, even better than the treacherous mountains and deep valleys.

The helmsman was nowhere to be seen, probably hiding in the revolting toilet, but the pirates didn't care where he was. They were focused on the passengers. In a matter of minutes, they had made half the passengers surrender all their valuables (which was also surprisingly entertaining, as who would expect an S-phone 4 from a beggar?).

"Boy, the thing on your shoulder! Put it into the sack!", demanded a stocky bandit after I showed him I was literally penniless.

"It's a solar cell, are you sure you want it?" I said.

"I don't give a damn what it is. JUST PUT IT INTO THE SACK!" His hoarse, booming noise drew the attention of another lean pirate, who turned around.

"Leave him alone," demanded the thin figure with all the coldness of a glacier.

"What? So that you can have his prize for yourself?" the fatter pirate replied haughtily.

"Have you got seawater in your ears? The thing's got a damn tracker on it. If you insist on taking it, I'll feed you to the dolphins!"

Both of the men automatically positioned their hands on their guns and glared intensely at each other.

A bead of sweat dropped from the bushy eyebrow of the chunky man onto my palm. Ten seconds passed, as slowly as thick syrup dripping from a spoon, but soon the pirate beside me conceded. "All right, but I'll tell the boss and see if he'll beat you bloody for this," he snarled at the skinny pirate.

Once they had taken their spoils and left our boat, the stocky pirate was still staring at my solar cell as the tiny speedboat sped away and faded into the sea. Many passengers were sitting gloomily on their seats, while a few optimistic ones seemed to be relieved by the fact that there were no casualties.

"Well," Chong broke the silence, "I'm glad that wage day's tomorrow. They only took the watercress I bought from the sea market." I laughed as I pictured the chunky pirate carrying watercress like a housewife, while other passengers, not yet recovered from the ordeal, shot bewildered glances at me.

I was home, finally. The soft, black solar cell lay promisingly on my shoulder, warming up under the sunshine as if it, too, was eager to be used.

The slum was a labyrinth of floatainers, floating containers that were altered for residential purposes, while underwater there was also a maze of water pipes, propane pipes and very rarely, cables, which, thanks to their abysmal insulation work, were known to be a hotspot for collecting electrocuted fish.

But this place was no longer unbearable for me, and instead I saw it as a gold mine. Everywhere was brimming with opportunities, from selling electricity directly to powering the long-abandoned desalination system and then making a profit from the precious clean drinking water. But first and foremost, there was my family.

The creaking of the wooden tier sang the loveliest melody I'd ever heard as I rushed home.

"Mum, Dad, I've got it, I've got it!"

Mum, boning a fish on the floor, looked up and grinned widely.

"Be quiet, grandma's having a nap," Dad said, trying to be stern, but hardly managing to hide his excitement. He had taken his only discretionary holiday in the year to witness this moment.

"So, shall we start?" he asked.

I moved the bunk that was blocking the input of the floatainer's powering system (every floatainer came with this system, albeit redundant most of the time because electricity was too expensive. Grandma always joked that it was like having a display cupboard with nothing to display).

Dad, usually weary from being overworked, was energetically scrubbing the built-in lamps that were so thickly covered with dust that they blended in with the grey ceiling. Chong volunteered to clean the rooftop, which had become home to flocks of pigeons and seagulls.

The solar cell rested on my shoulder as I climbed onto the rooftop, my heart pounding. I had all the power and the answer to all my problems on my shoulder.

I meticulously uncurled the panel, even more carefully than an archaeologist unfolding an ancient scroll. Mum, Dad and Chong were all staring nervously. Nothing happened. I felt faint, but a moment later a "BEEP" erupted from the panel.

The dull, black surface glowed and became a giant display screen, with the words, "Start? Yes/No", on it.

"Dad, are all the cables connected?" I asked, like a kid who had been aching to unwrap his present, but was unsure whether he wanted to spoil the pleasure of anticipation itself.

"Everything checked, go ahead! The waiting's killing me!" Chong yelled before Dad had a chance to reply.

"Here we go," I murmured, and pressed the button.