In the US, young African Americans need to learn that the world is not fair - it's a matter of life or death

One mother, Lonnae O’Neal, doesn't want to tell her son that he will be treated differently, and so he must act differently

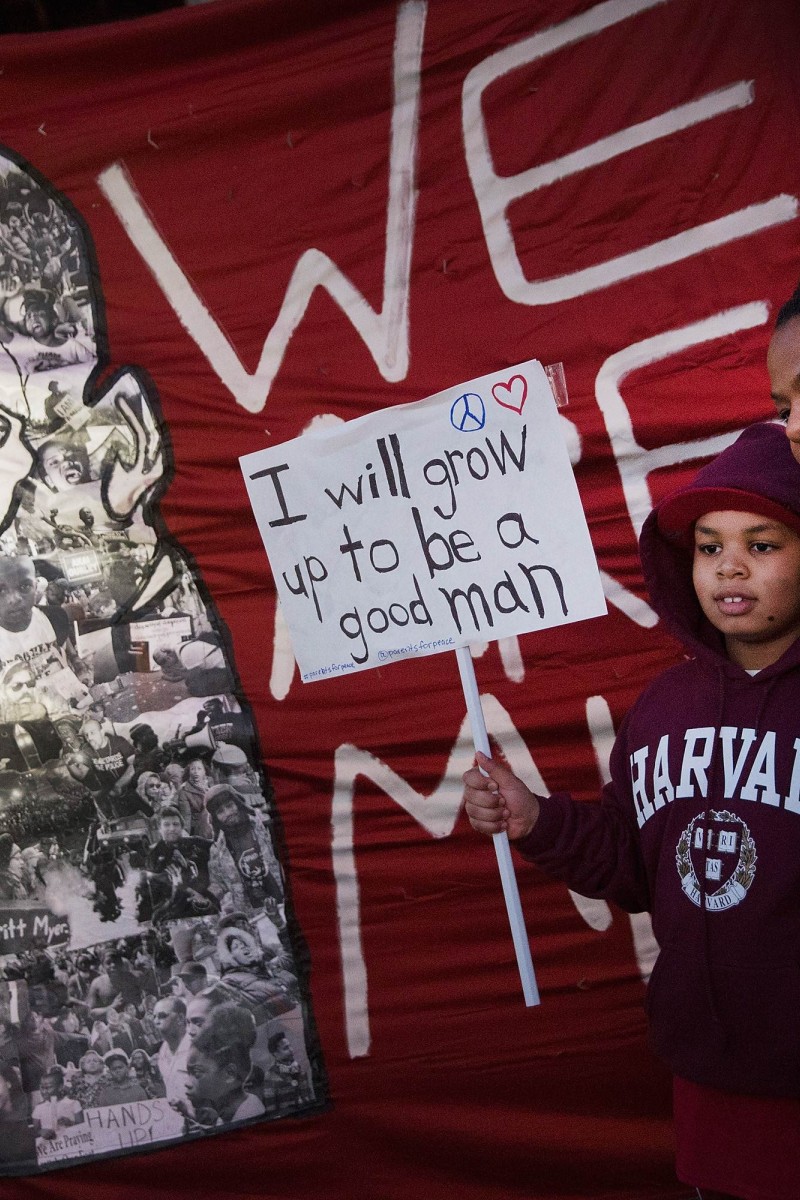

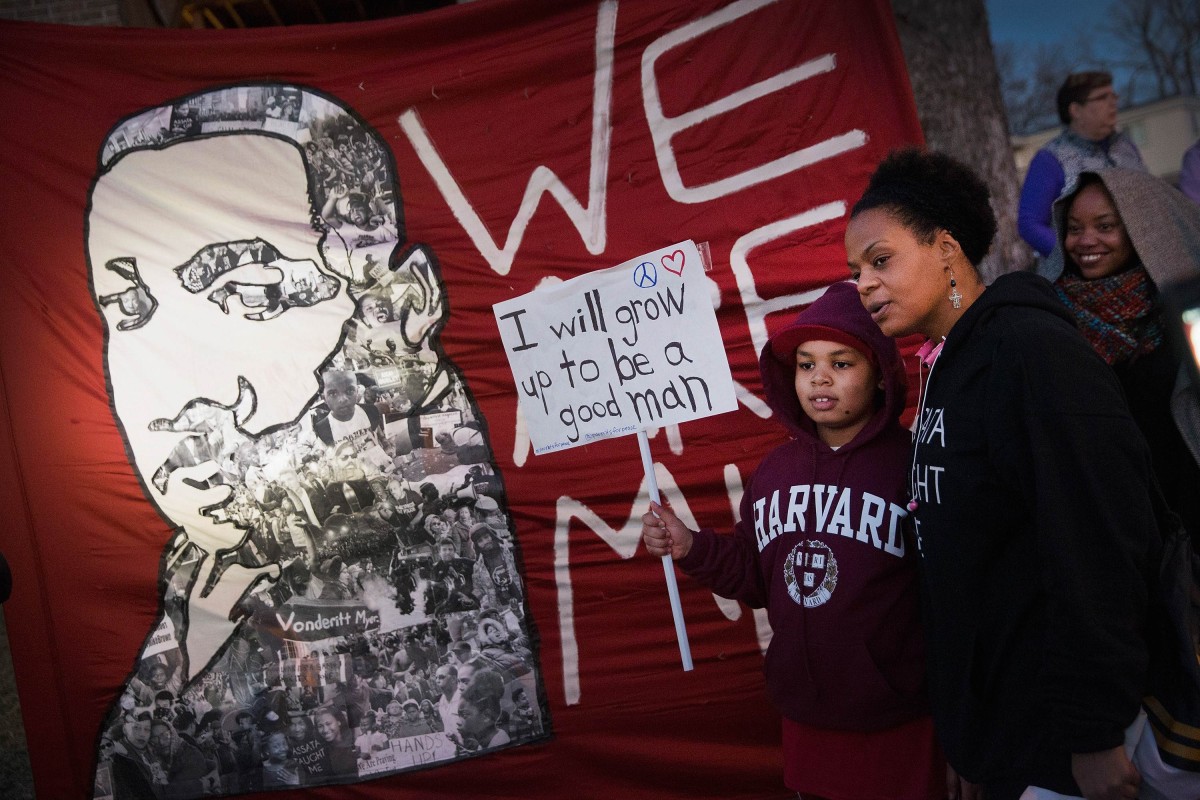

Demonstrators protest next to the Michael Brown memorial on Martin Luther King Jr. Day January 19, 2015 in Ferguson, Missouri.

Demonstrators protest next to the Michael Brown memorial on Martin Luther King Jr. Day January 19, 2015 in Ferguson, Missouri. I called home a few weeks ago and my 12-year-old son picked up the phone. "Whassup? Who dis?" he asked, dropping his voice low.

"Satchel?" I chided. "What is your problem?" He giggled.

"Oh, hey, Mommy. How are you?"

I paused for a moment to appreciate the space my son was in. A space between sweetness and swagger. A space of video games and anime, of his first coed parties, and his mother’s gathering dread. It is winter in a year (a decade, a nation) of black boys down, and my son grows tall.

Satchel and I talk about his allergies to shellfish and, seemingly, showers. We talk about his discomfort with "girl topics" in health class, and whether I believe Ray Charles ever knew Al Green. What we don’t talk about is Ferguson, about the cop who shot the unarmed teenager in Missouri. I have not talked with him about Michael Brown. Or Trayvon Martin or John Crawford III or Levar Jones, et al.

I have not had "The Talk" with my son.

In 1994, Washington Post columnist Donna Britt wrote about "the talk" and needing to tell her 12-year-old son repeatedly "the rules that every child - but especially a black one - should know: Never be cocky or make any fast moves with a cop."

Last August, The Post carried a poem, The Talk, by Jabari Asim, executive editor of the Crisis magazine and former editor of The Post’s Book World.

"It’s more than time we had that talk

"about what to say and where to walk,

"how to act and how to strive,

"how to be upright and stay alive. ..."

I know what the moment calls for, but put yourself in my place. Try to wrap your mind around having this ritual conversation with a child, with your child, to prepare him for a world where people have a conditioned response to him. To prep him for their recoil. To impress on him that it could be a matter of life or death.

Say that to your son, even though he teared up last week when a teacher accused him of being unfocused in class. Say that people might suspect him, and kill him, even if he does nothing wrong, let alone if he does average, stupid teen stuff like smarting off, or cutting his eyes, not to mention shoplifting, smoking pot or jaywalking.

I don't have the words

I have not had that talk with my son, and right now have no plans to. An abdication, some will say, and I take that point. It’s just that I curl up when I think about it. What words will keep him safe when white men can’t manage their anxieties about him? And he already has to contend with nihilism among other young black men? And everybody has a gun.

I don’t have words that will give him the judgment and self-restraint of a 40-year-old man when he’s in seventh grade. Not even if his life depends on it. I don’t have the words to quell his anger if he feels like he’s being treated unfairly, and anger is called for. Most of us can’t even stop ourselves from getting mad when somebody cuts us off at the intersection. It is monstrous to expect preternatural calm from a teen in order that he not get shot.

I watched the video of Levar Jones being stopped for a seat-belt violation by a now-fired South Carolina trooper. Jones reaches for his wallet, the trooper shoots him, and Jones falls to the ground and apologises.

"I’m sorry," Jones says. "I’m sorry."

And I put my hands up between my face and the computer screen. Fifty years after Martin Luther King compelled us to imagine - and work for - a nation of fairness, equality and justice, I must strip the innocence from my son forever.

No! No! No! No! No! No! No!

I will not have the talk with my son. I have a different approach. It is admittedly a short-term plan. It relies on the fact that he’s 12.

My strategy is laid out in that old, sweet baby-clothes commercial. I can still hear it playing in my mind. "If they could just stay little till their Carter’s wear out." My hope for my son is much the same.

If he can just stay 12 until the world changes.