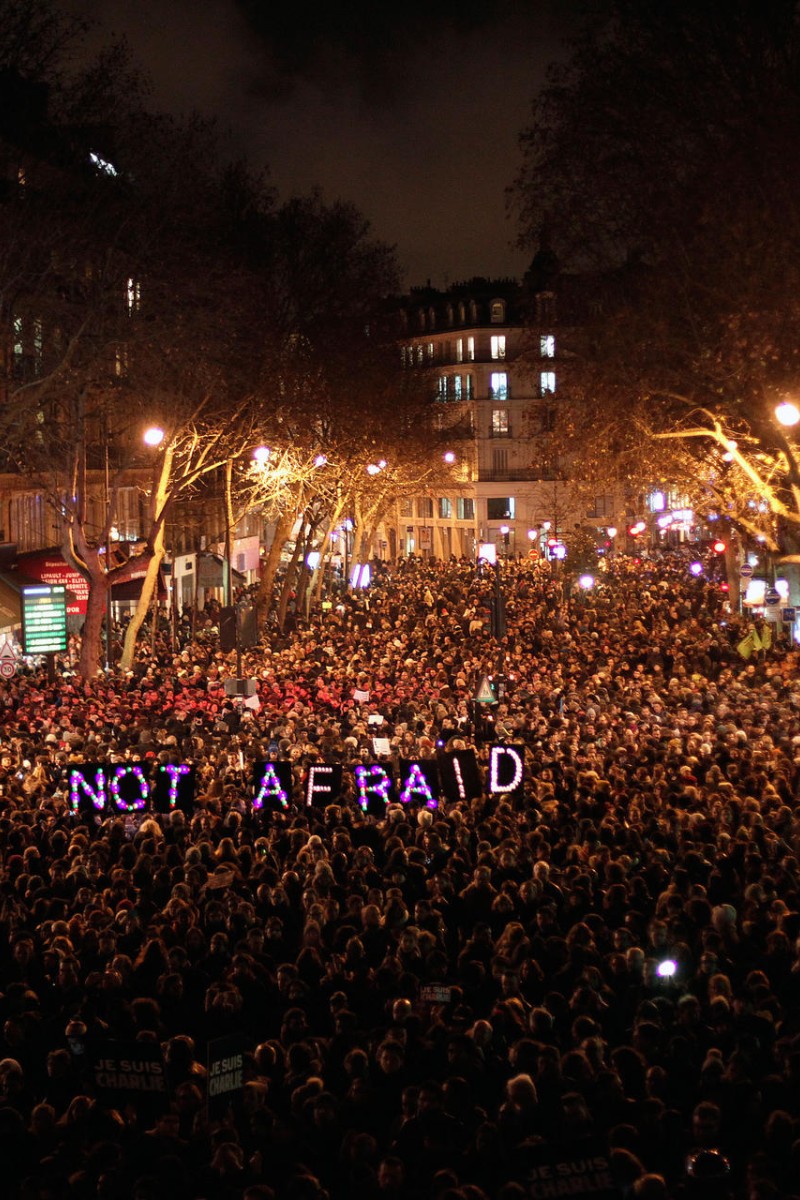

The attack on Charlie Hebdo is an attack on free speech itself

Published:

The Guardian

Listen to this article

There is no justification for these murders because the right to free speech must also include the right to offend

The Guardian

|

Published:

Sign up for the YP Teachers Newsletter

Get updates for teachers sent directly to your inbox

By registering, you agree to our T&C and Privacy Policy

Sign up for YP Weekly

Get updates sent directly to your inbox

By registering, you agree to our T&C and Privacy Policy