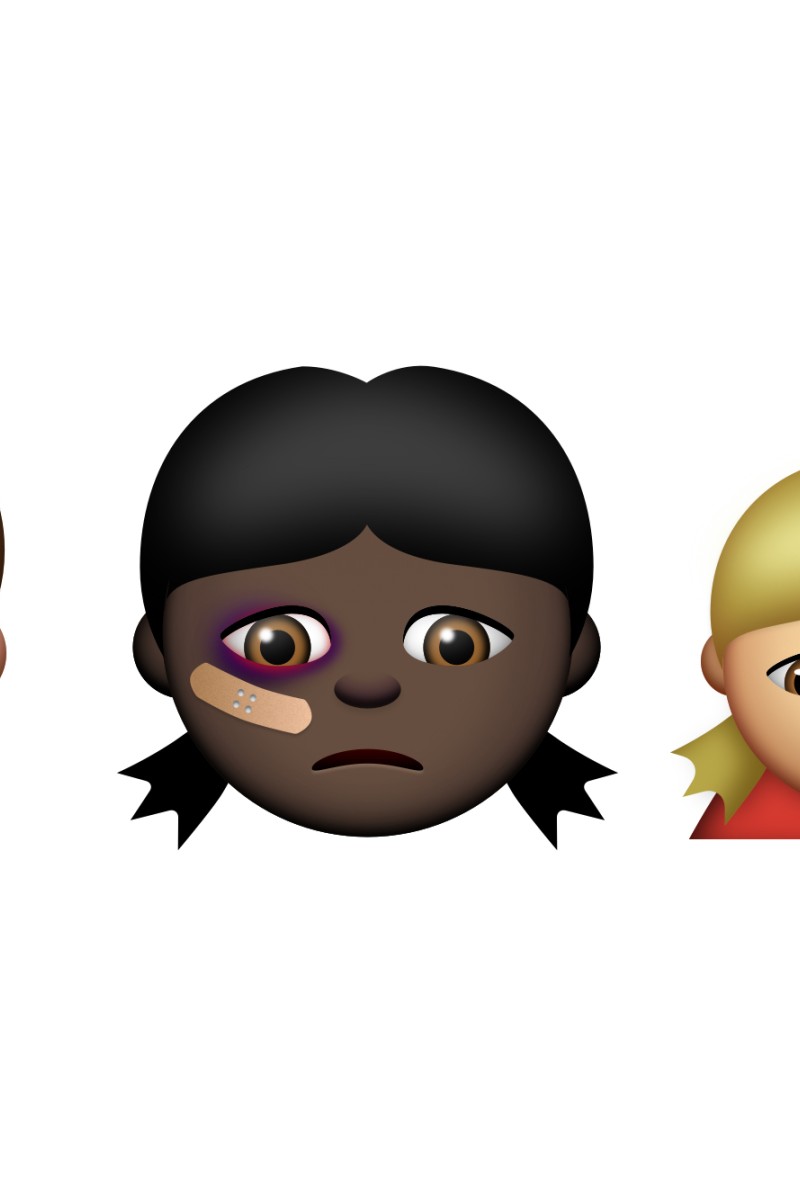

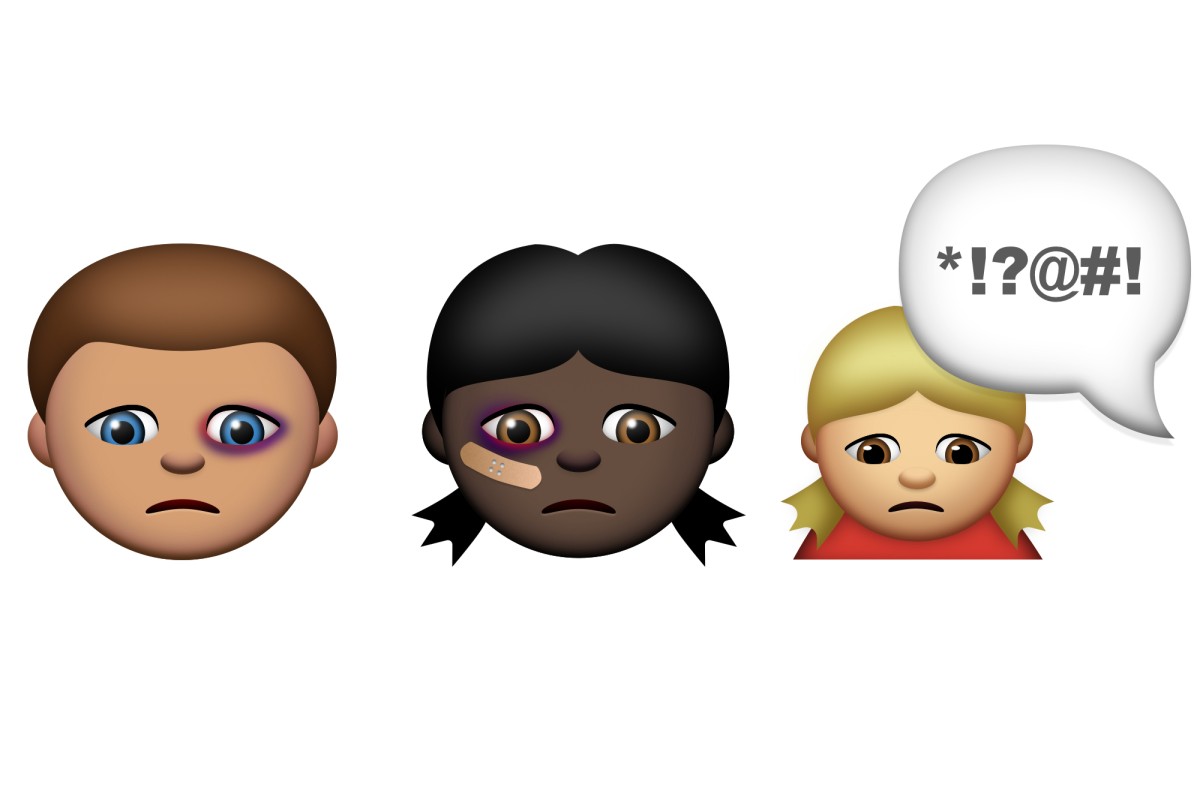

The new emojis reflect social problems.

The new emojis reflect social problems.You can say a lot with emojis; and now a Swedish children’s rights group hopes the little digital icons can make it easier for children to talk about abusive or difficult situations.

The group, BRIS, made an app called Abused Emojis. Instead of piles of smiling poop, grinning yellow faces, or a ghost sticking its tongue out, Abused Emojis include icons such as an alcoholic father looming over a sad child, a baby being slapped, or hands with cuts on the wrists.

The idea is that the app, which is currently available for iOS, will make it easier for young people to talk about abusive situations without having to put them into words, says Silvia Ernhagen, director of communications and advocacy at BRIS, which also runs a helpline for children.

“Emojis could help children start showing their emotions and start to lift the lid on difficult issues,” Ernhagen says. “We find that sometimes they have difficulty putting their experiences (into words).”

A 1998 article in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied concluded that when some children were asked to draw something about an emotional experience, they gave twice as much information as children asked to just talk or write about that experience.

May Chan Siu-mei, who works with children in Hong Kong, is an art psychotherapist and trauma specialist at The Boys’ & Girls’ Clubs Association of Hong Kong’s Jockey Club Trauma Treatment Service for Children. She says emojis can make it easier for children to communicate.

“These images can serve as a kind of ‘language beyond words’. It makes it easier for young people to describe an internal conflict, rather than having to write a lot of words,” Chan says. “It also makes it less awkward or embarrassing for a teenager to say something personal.”

However, Chan cautions that using the app may not be a substitute for two-way communication, because there’s no way to ensure when and how a person receiving the message will respond. For example, if a child going through a hard time sends a message, and no one responds even after a few hours, the child might wonder if anyone is going to help.

Chan says, while not a total solution, the emojis are a good place to start.

“We shouldn’t dismiss tools like this as something that’s just for fun, or that if you need help, you have to go to a social worker or call a hotline,” she says. “That’s a very outdated way of thinking. This just opens another door for people like us who are serving young people. This is a good place to start a conversation.”