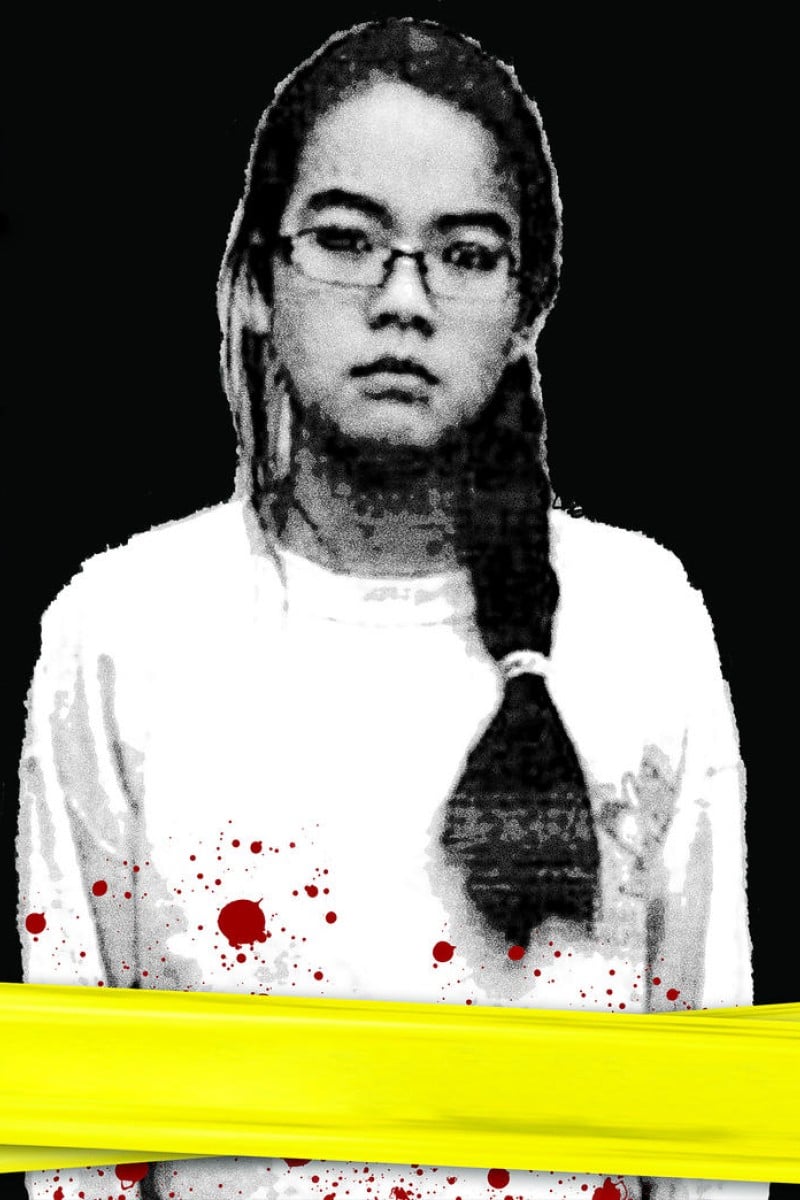

Jennifer Pan said she had straight As, scholarships, and a great job - except she didn't. And when her parents found out she'd been lying the whole time, Jennifer tried to have them killed

For a while, Jennifer Pan’s parents regarded her as their “golden” child.

The young Canadian woman, who lived in the city of Markham just north of Toronto, was a straight A student at a Catholic school who won scholarships and early acceptance to college. True to her father’s wishes, she graduated from the University of Toronto’s prestigious pharmacology program and went on to work at a blood-testing lab at SickKids hospital.

Pan’s accomplishments made her mother and father, Bich Ha and Huei Hann Pan, brim with pride. After all, they had arrived in Toronto as refugees from Vietnam, working as laborers for an auto parts manufacturer so their two kids could have the bright future that they couldn’t attain for themselves.

But all of Jennifer’s great success was just an elaborate lie. Jennifer, born in 1986, failed to graduate from high school, let alone the University of Toronto, as she had told her parents.

She’s now serving a long sentence in prison for plotting with hit men to kill her parents. But the full story of this troubled young woman is just now being told as a complete and powerful narrative by someone who knew her.

The inside story

Reporter Karen Ho detailed the intricate web of deception that her high school classmate spun to prevent her parents from discovering the unimaginable: that their golden child was, in fact, failing. Using court documents and interviews, Ho pieced together Jennifer’s descent from a precocious elementary schooler to a chronic liar who forged report cards, scholarship letters and university transcripts – all to preserve an image of perfection. The headline: “Jennifer Pan’s Revenge: the inside story of a golden child, the killers she hired, and the parents she wanted dead.”

Their high school, Ho wrote, “was the perfect community for a student like Jennifer. A social butterfly with an easy, high-pitched laugh, she mixed with guys, girls, Asians, Caucasians, jocks, nerds, people deep into the arts. Outside of school, Jennifer swam and practiced the martial art of wushu.” But Ho would “discover later that Jennifer’s friendly, confident persona was a facade, beneath which she was tormented by feelings of inadequacy, self-doubt and shame.”

Among the signs that few saw were cuts on her forearms, self-inflicted.

The lies begin

The real Jennifer never enrolled in university. She never even graduated from high school.

“Jennifer’s parents assumed their daughter was an A student,” wrote Ho in the article. “In truth, she earned mostly Bs – respectable for most kids but unacceptable in her strict household. So Jennifer continued to doctor her report cards throughout high school. She received early acceptance” to Ryerson University in Toronto, “but then failed calculus in her final year and wasn’t able to graduate. The university withdrew its offer. Desperate to keep her parents from digging into her high school records, she lied and said she’d be starting at Ryerson in the fall. She said her plan was to do two years of science, then transfer over to U of T’s pharmacology program, which was her father’s hope.

Hann was delighted and bought her a laptop. Jennifer collected used biology and physics textbooks and bought school supplies. In September, she pretended to attend frosh week. When it came to tuition, she doctored papers stating she was receiving student loans and convinced her dad she’d won a C$3,000 (HK$17,000) scholarship. She would pack up her book bag and take public transit downtown. Her parents assumed she was headed to class. Instead, Jennifer would go to public libraries."

When it came time for the University of Toronto graduation ceremony, Jennifer told her parents there weren’t enough tickets to go around and they could not attend.

But ultimately, they got suspicious and began following her. That’s when they learned the truth.

The truth comes out

When she confessed her lies, life in the Pan household quickly began to unravel.

Bich and Hann had raised Jennifer and her brother, Felix, to believe in the supreme importance of academic success, and they restricted their activities to ensure nothing less. Jennifer, whose high school life included numerous extracurricular activities, like figure skating, piano, martial arts and swimming, in addition to long nights studying, was forbidden from attending parties of any kind. Dating was out of the question.

When Pan’s parents learned that all of their efforts had been for naught, they placed further restrictions on their now-adult daughter. No more cellphone. No more laptop. No more clandestine dates with her boyfriend, Daniel Wong.

While she eventually gained more freedom, Pan stayed angry. She thought about how much better her life would be without her parents. And so, with Wong’s help, she plotted to kill the two people who had made her life like “house arrest.”

Frustration turns to murder

In November 2010, in a planned murder disguised to look like a robbery gone awry, Pan played the part of helpless witness as three hired hit men, David Mylvaganam, Lenford Crawford and allegedly Eric Carty, fatally shot her mother and severely wounded her father. She called 911, distraught, to bolster the illusion.

And the initial headlines supported it: “Markham’s Bich Ha Pan was gunned down inside her own home during what appears to have been a random home invasion,” reported the Markham Economist & Sun. “Markham killing shocks neighbours.” “Home invasion suspects ‘pose very real danger’; Markham police warn residents after woman killed in random attack,” said the Toronto Star.

But police officers investigating the case caught on within a couple weeks. This lie – that an immigrant couple was shot by random burglars and not through the will of their daughter – would have to be Pan’s last.

This January, an Ontario court found Jennifer and her three-co accused (Wong, Crawford and Mylvaganam) guilty of first-degree murder and attempted murder. They were all handed life sentences with no chance of parole for 25 years. Carty, who has pleaded not guilty, will be tried separately.

A lifetime of pressure

While Jennifer’s trial was heavily reported in the Canadian press, it turned out to represent only a fragment of a more complex and tangled story, told by Ho.

Ho’s article, in part because it was reported and researched by a former classmate familiar with Jennifer’s life, offered an account of the complications leading up to her horrific deed.

“Ultimately, it’s a horrible crime,” writer Ho said in an interview with The Washington Post. “But because so many people have gone through the experience of growing up like Jennifer, it’s not unfathomable to them that someone would just break.”

Ho said the expectations placed on many Asian-American children have a huge long-term impact on their ability to withstand failure. “You just grow up chronically afraid. This buildup of lies is because Jennifer felt like the alternative was just unfathomable.”

“The more I learned about Jennifer’s strict upbringing,” Ho wrote, “the more I could relate to her. I grew up with immigrant parents who also came to Canada from Asia (in their case Hong Kong) with almost nothing, and a father who demanded a lot from me. My dad expected me to be at the top of my class, especially in math and science, to always be obedient, and to be exemplary in every other way. He wanted a child who was like a trophy – something he could brag about.”

Jennifer’s case tells the story of Asian immigrants’ dreams turned to violent nightmare. The saga is fraught with many of the tensions that have pervaded discussions surrounding Asian immigrant communities in recent years, from the “model minority” myth to the debate over whether Asian parenting yields better results. As attention is drawn to the mental health issues among Asian-Americans, it now also fuels questions about how much pressure is too much.

Unacceptable behaviour

It’s a mistake to take one case and generalize or stereotype, noted Jennifer Lee, a sociology professor at the University of California Irvine who specializes in Asian-American life in America. And she said, it would be a mistake to attribute Jennifer’s troubles to “tiger parenting”.

Jennifer’s story is an extreme case. “It’s so easy to blame immigrant parents,” said Lee, who co-authored the recently released book The Asian American Achievement Paradox. “The danger of highlighting cases like Jennifer’s is that they contribute to a misconception that all Asian-American kids experience this extreme pressure and are mentally unstable.”

But she said, “Jennifer’s parents certainly had a role in making her feel trapped, but I think there’s a broader discussion to be had about the expectations that teachers, peers and institutions place on people like Jennifer to fit that stereotype of the exceptional Asian-American student.”

Since it was published last Wednesday, Ho’s article has been widely shared on Facebook, striking a powerful chord with Asian immigrant children in Canada and the United States who have taken to social media to share tales of their parents’ high expectations and the crippling fear associated with not meeting them.

In the Reddit discussion of the story, one user, who created a new account in order to comment anonymously, writes: “ … this story did a number on me, because my life used to resemble hers. I come from an Asian family, with a lot of that immigrant parent mentality. I was an exceptional student in high school, getting scholarships for university and having my pick on which to attend. And then it went downhill from there.”

He also lived at home, pretending to have a respectable job: “[My parents] gave me everything, sacrificed so much for my success, and this was the result.” But unlike Jennifer, he adds, “I accepted those conditions from my parents to fix my life … I don’t have any sympathy for Jennifer Pan because I feel like I was in her shoes. After her parents found out, her dad reacted similar to mine, so did her mom.”

But, he wrote, “I used the opportunity to get my life back, she used it to wreck hers.”